7 November Bradan (2,850m) – Ongre (3,322m)

We’ve passed the 3,000m mark and we can certainly feel it. As soon as the sun disappears the temperature plummets. Today was a wonderful day. Having covered so much extra distance yesterday, we were able to lie in till 7.00am. The sun was coming through the cracks in our wooden windows. I realised I felt hungry – a sure sign of full recovery. We joined the others for a large breakfast. Then came the sense of purpose and communal spirit as everyone packed up ready for another day on the trail. As I was heading up the steps to the loo on the other side of the track from our guest house, I heard someone call my name and turned to see Canadian John. He had spent the night in Bradan’s second guest house. Great! We were keeping pace with the faster walkers, although we couldn’t quite match Serge. John reported that he had surged ahead to Pisang the previous day. He’s probably half way to Manang by now so I guess that’s the last we’ll see of him.

Our path led through a beautiful pine forest. The wind blew bitterly as we headed out of Bradan but, as the sun grew higher, it thawed our frozen limbs and by about 9.00am, we stopped to rest in warm, green filtered sunlight. Eugene, Narayan and I posed sitting on a carpet of pine needles while Beth took our photo. A little further on, we met a New Zealand couple we vaguely recognised and joined them for a drink. You are advised to drink as much as you can at high altitude – 4 litres per day if possible. You tend to breathe in short sharp breaths in the thin, cold air which makes you dehydrate more quickly than usual. We had all been trying to step up our quantities of tea and iodine-flavoured water as we climbed higher. This had the predictable consequence of making everyone have to pee all the time. This is especially annoying in the middle of the night (i.e. about 10.00pm since we are usually tucked up in our sleeping bags by about 7.30pm!) You are awakened by a series of breathy curses as one of your room-mates stumbles around hunting for a torch and the door key. S/he stumbles down the rickety wooden steps and across the inevitable obstacle course to the freezing wastes of the toilet. (Forget the flushing system and wash-basin!) Ten minutes or so later s/he then comes crashing back up the ladder, now three-parts awake and waxing lyrical about the beauties of the star-filled sky over the mountains. Now, thoroughly awake, you, or another room-mate, realise that you just HAVE to go and the whole rigmarole starts again.

A golden mongrel dog began to follow us as we continued through the trees. Towering mountains appeared periodically. I wished all trails could be like this. Presently, the trees gave way to scrub and our path led past a dramatic bowl in the mountains. Smooth grey escarpments rose on three sides and in the middle was a helipad. I felt surprising full of energy and rushed over to the stone ‘H’ in the centre and pretended to be a helicopter for the benefit of the camera.

The approach to Pisang was very pretty. For the first time the scenery was what I imagined was Tibetan. We could see the flat-roofed houses of upper Pisang in the distance. Prayer flags fluttered from every roof. Red berries stood out against a blue and brown landscape with the tip of Pisang Peak an ice-cream cone of bright white behind. Pisang was LP’s recommended stop for the night. However, it was only mid-day so we decided to stop for a longish lunch while it was sunny, then proceed to Ongre, a good way on to Manang. By now we had concluded that early arrivals and long evenings could be cold and boring. After our brush with food poisoning in Bagarchhap, we really preferred to stay in smaller places with fewer trekkers. It was easier for Narayan to check up on whether the cooks had washed their hands, waits for food were shorter and there was more chance of a place round the family fire.

I was starving again. We joined Jyoti and Baishali the two Nepalese girls who were sitting in the sun eating momos outside the first tea-house we came to. They were going on to Ongre too. They had managed to confirm their plane tickets from Ongre to Pokhara for the following morning. They were both medical students from Kathmandu but were currently doing their practice down south in the Terai. Baishali was dark and I had thought she was Indian but Jyoti could have been from anywhere. She was stunning with dark brown hair and startling green eyes. Police often stopped her to ask for her trekking permit at check points, not realising she was Nepali. Both girls spoke fluent English.

Narayan, as usual, infiltrated the kitchen. We sat outside in T-shirts enjoying the sun and feeling reassured that we had clocked up a third thousand metres and were still feeling fine. I wasn’t really worried about altitude sickness yet since I’d survived at a height of nearly 4,000m on several previous occasions, but Pisang represented the highest point in Eugene’s life so far. Clare and Rob arrived and we all ordered momos. These are a Tibetan delicacy and consist of little pastries stuffed with spicy meat or vegetables (in this case, potatoes) then either steamed or fried. They are usually filling, tasty and a welcome alternative to dahl bhat.

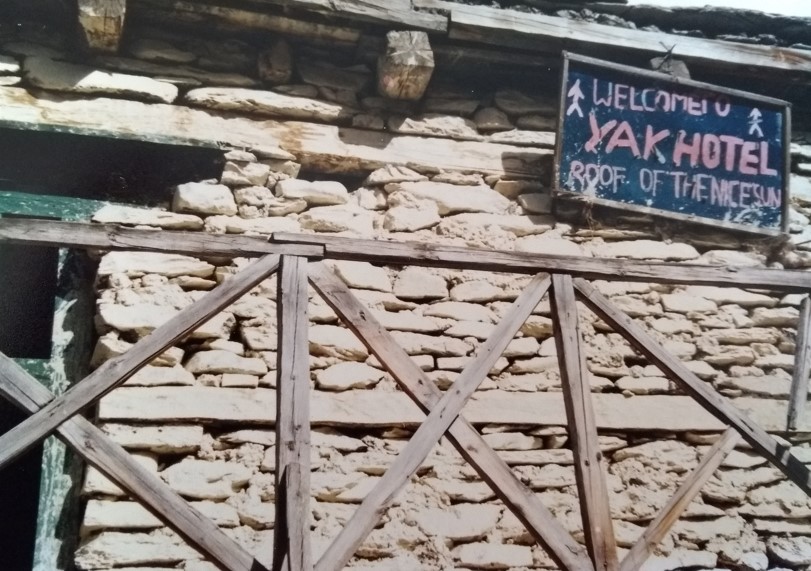

Clare and Rob made their base in Pisang for the night and, with a wish to see them in Manang, the rest of us wound our way onwards and upwards to Ongre. The light faded quickly as the afternoon wore on and, under a dimmer sky, the landscape became increasingly Tibetan. Gone were the lush green paddy fields of lower lands, the strings of Diwali marigolds and the human haystacks. Here was a drier country of burnished browns and golds backed by grey cliffs and ice-bound peaks. People were far fewer. They were Buddhists and had the flat Mongolian features of their northern neighbours. They were more likely to be herding cattle or carrying prayer wheels than hefting stacks of cut grass. We sighted our first Tibetan trinket stall and stopped there for tea. It sold woolly hats, scarves, enormous knitted socks, turquoise jewellery and religious relics of dubious antiquity. In a cowshed next door sat an old man in full Tibetan regalia spinning a prayer wheel. Eugene asked to take his picture but changed his mind when the old geezer wanted 300 rupee for the privilege.

We found the others (i.e. the Austrian trio, Paul, Irena, Jyoti and Baishali) at the Maya Lodge in Ongre. Like most other lodges the Maya claimed to have a hot shower. Don’t get too excited. If this exists, it is normally in a wood and corrugated iron hut with a mud floor. At least the Maya did provide a whole bucket per person of hot water. It was far too cold to strip completely, but at least we could get selected bits clean.

As the temperature dropped everyone congregated around the cooking fire. Beth always seems to spend loads of time doing Buddha knows what in our freezing cold room. Eugene and I prefer warmth and company, so we joined Paul and Irena and a mad Nepali called Madhu at the fireside. I got talking to Madhu who gave a long diatribe about the evils of the Nepali political system and against the world in general. He was already three parts pissed. He was travelling with a Finnish guy who had been stricken with altitude sickness on the way to Thorong Phedi. Tales of people being forced to return from where we were heading worried me slightly. However, when the Finn finally emerged for a meal, he was the unhealthiest looking individual I’d ever seen. He had sweaty, spotty skin and was skeletally thin. He had been suffering from various stomach complaints and flu all the way. I tried to keep a safe distance from him in case I caught anything.

We moved to the table to eat. I tried fried potatoes and yak cheese as recommended by mad Madu. Delicious! Beth, as always, caused local angst by ordering nothing but a bowl of boiling water. She was lugging vast amounts of packet soup and muesli, preferring not to risk the local nosh. I don’t know how she walked for 7 hours a day on it. I was almost permanently starving. Over dinner Jyoti and Baishali enlightened us a little about the caste system amongst Nepal’s Hindus. They admitted it was a lousy system. They were both Brahmins, the highest caste and told us that you could always tell Brahmins by their long noses. The conversation took a gory turn when they explained that because Hindus are always cremated, there was a severe shortage of bodies donated to medical science. This means that medical students have no conveniently formeldihyded bodies to study and practise on. Instead they have to go out and find their own. The only ones available come from unclean graveyards. Yuck! It’s hard to imagined Jyoti and Baishali, who seem such genteel young girls, going out with a shovel to rob graves as part of their course. Before I had nightmares, I moved back to the fire to write my diary in the company of the family elders peacefully spinning their prayer wheels and muttering ‘Om mani padmi hum’ – ‘the jewel in the heart of the lotus’. No-one seems to know quite what that means but I felt really privileged to be in a remote mountain village being part of all this.

Leave a Reply